Blood Ink

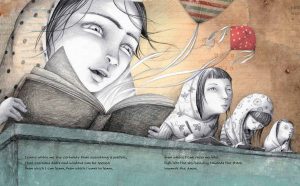

Illustration by Sonja Wimmer

By Carolyn Coe

(Voices for Creative Nonviolence)

ZARGHUNA has inked a drawing at the mound of her thumb. I draw here when I’m in pain, she says, pressing where the ink has just dried.

Her exam was scheduled for 8 a.m. But when she got to the university, she learned that the exam was postponed. She asked her classmate Hussain if he’d finished his homework, a video report for another journalism class they share.

No, he told her, but he’d do it that day. He was going to bring his camera to a demonstration in the western part of the city, a demonstration for new electrical transmission lines to be routed through majority Hazara areas.

About twelve hours later, a fellow classmate calls Zarghuna to say that Hussain is dead. He had gone to the demonstration with Hussain.

Zarghuna sits beside me. He had two daughters, she tells me. He was a quiet person, and older than some of her other classmates. She imagines how Hussain might have finished his degree this year with her had the exam occurred as scheduled.

News about the explosion in Kabul first came to Zekerullah from his brother in Bamyan, a province hours away.

Are you okay? his brother asked.

I was asleep when the phone rang, Zekerullah said. Zekrerullah was upset about hearing the news just upon awakening, so he just said,

I’m okay, and abruptly cut the line.

Before the blast, Hamad calls his brother to find out where he is. Abdulhai didn’t come back home for lunch. Pul-e-Surkh, Abdulhai says, a nearby neighborhood.

Minutes later, after learning about the explosion, Zarghuna rushes in and asks where their brother Abdulhai is.

Pul-e-Surkh, Hamad answers.

But where? Zarghuna asks, desperate for his exact location.

So Hamad calls Abdulhai again.

The need for details accompanies crisis.

Three of the boys, each of them Hazara, go to two hospitals to try to donate blood for the 230+ wounded. They are joined by Nawid, a Tajik friend. But the first hospital already accepted all it could and the second declined their offer.

People in the streets give drivers money to take willing blood donors to the second hospital, 45 minutes away. Outside that hospital, others pay for people’s taxi fare back home.

En route, the boys pass by the roundabout where the explosion occurred. There were so many shoes, Abdulhai tells me as soon as he returns. He describes a woman, crying, crouched down to light candles on the blood-soaked pavement, the air smelling of blood.

Tajik-style hats left behind on the scene suggest that not only Hazaras had been demonstrating.

Each person responds to the event in his/her own way. One sits in darkness. One skips dinner. One goes to bed early. And one stands with slumped shoulders, his body caved in profound sadness.

Hamad tells Hoor, Every Afghan family has experienced this, and I have lost three.

This morning, we clean up the garden where tomatoes, radishes, hot peppers, and basil grow. As I pull up morning glories twined around a pair of rose bushes, Zarghuna laughs that the roses were prisoners that I’ve freed.