For Russians with Love (A Photo Journal)

By Hakim Young

With a holiday smile, and a tease in her eyes,

Yalta School Twelve’s ex-principal, Valentina,

( on the right in the above photo)persuaded us,

“Let us strengthen our ties!

You see, it’s our only request, our only wish.

We want to live in peace….”

with EVERY ONE.

She reminisced about how

“We had a club of international friendship…”

though, wow! “there were no computers then….”

Who is guilty of today’s strained relations?

“Journalists…..and the media!” Valentina pronounced.

Her conclusion reminded me to doubt and question,

to circumvent and to overcome mainstream media.

If we wished to understand more about anyone,

beware not of Valentina, but of popular news!

She left a little earlier

to “Skype with my grandson who’s studying in the States!”

Julia ( right ) and Irene ( centre ) with me, wearing the Borderfree Blue Scarf.

Julia, a university student of foreign languages,

said that both “the young and the old are ready to

make peace in the whole world…”

but “there’s a lot of brainwashing in mass media….”

If you met Julia and Irene and other Russian youth that Crimean morning,

your mind would go through a sort of ‘healing’,

and you would think like I did, “What nonsense that

some politicians demonize Russians as ‘barbarians’!”

Public opinion and consciousness,

especially among millennials,

is awakening to ask, “Who do the politicians think they are kidding?”

The age of unaccountable kings and their cronies is passing away.

The media moguls will tremble

if we built massive, worldwide, borderfree friendships.

That’s how ready we are,

when we come together.

From left to right: Samlev, Aslan, Manchenko, Eugenia

and Anton, meeting a few U.S. delegates.

Aslan is a Crimean Tartar. Samlev is Crimean Armenian.

The rest are from Yalta, Crimea.

Eugenia , Samlev, Aslan, Manchenko, and Anton

are Russian youth who gifted me with summer hope:

they recognize but aren’t tied down to their diverse ethnicities,

they are children of the internet revolution who find propaganda laughable,

they are open to change,

they are energetic and fun,

they aren’t closed to humanity and love.

Abolish nuclear weapons?

Anton said, “Talk on the same ( equal ) level”

“Agree…”

“…on a vision which includes protection of the environment’.

Retired Deputy National Intelligence Officer and member

of Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity, Elizabeth

Murray, with a Russian Veteran, Ishuk, at a ‘Swim for Peace’ event in the Black Sea of Crimea.

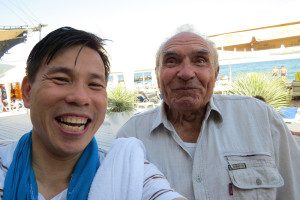

Russian war veteran, Medved, initially seemed unapproachable to me in his military uniform

But at the ‘Swim for Peace’ event, faced with language barriers, he was a spring of energy!

And he shook everyone’s hands!

That’s how we can share laughter and solidarity with the new generation of soldiers.

I saw in Medved’s hearty smile

a desire

to live and swim freely

and to be able to embrace everyone.

One of the veterans said, “What the state wants is not what the people want…”

I sensed that inside their hard historical experiences lay

waves of emotions

and many moons of tears

which gravitate tides beyond the Black Sea.

What can I do for these and other veterans?

When Medved gripped me in one of his palms,

I felt the unspoken, twilight moments of many a soldier

who wish that the war would finally be over.

I knew then that he wouldn’t mind

if our generation worked to abolish war.

He would round up soldiers, their wives and their mothers

for refreshments by the beach.

The Simferopol Rotary Club arranged a meeting with Simferopol city officials, the most prominent theme being the ‘handshake screen’ on both sides of the room. None of the Russian or U.S. participants that day could possibly go to war with one another!

A waiter, Sergei, provided wonderful service to Vladimir Shevstoky, my new Russian friend on the delegation, at a lunch hosted by the Simferopol Rotary Club.

There are no ‘enemies’ where food is generously shared.

Alix ( right ) and Andrey ( left ) had chatted with one another at the lunch table using Google Translate! Technology has yet to be maximized to build personal relationships with real people.

Much was said at the oval-table Simferopol meeting,

including Ray McGovern testifying that,

“We cannot rely on our media in the U.S….

it’s very important for us to be able to speak from personal experience with

real people.”

As we enjoyed good food and company,

Alix and I chatted with Andrey using Google Translate.

I asked, “What do young people in Russia like to do?”

Andrey’s translated answer came

as an affirmation of what young people everywhere want:

‘work, leisure, sports, travel’.

If every American and Russian had decent livelihoods, enjoyed leisure time,

participated in sports and travelled to see people and places,

war could never be sold as ‘necessary’,

whatever the dispute.

Humans have so many more abilities

than just using force.

Renata, with her mom, Valerie, came to meet us at the ‘Swim for Peace’ event.

Renata was so happy to meet Americans for the first time.

Valerie had been worried, mainly for her daughter Renata,

when unrest began in Donetsk, Ukraine.

“I am responsible for her safety, her education and her health.”

Her words and manners were like a steel cushion,

soft yet strong.

As she showed me the dining hall of Yalta Artek,

a three-week Russia school camp to help children

‘study while exploring’,

she mentioned her vegetarian choice:

“I don’t feel comfortable with taking any kind of life…”.

“I teach my Artek students English not in the classroom,

but by exploring Crimea’s natural environment…

water, land, air, humans…”

It began to sound more like a curriculum on life.

Life for Valerie was recently rather tense;

she had become “depressed” in the Donekst unrest.

Coming to Yalta in Crimea was coming to a safe place

for her and 11 year old Renata.

“I will do everything so that she will be happy!”

Sevastapol, prized for and doomed by her waters, is home to one of Russia’s naval bases, perhaps sought after by other powers.

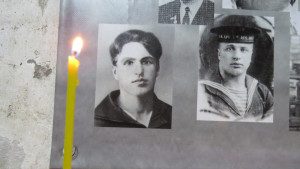

At the wall of the Memorial Museum 35th Battery Sevastapol, we lit candles… my eyes scanned all the faces, and I became curious about who was in the bottom left corner.

There he was. What was his name?

Too many names of war casualties.

Our tour through the museum was heavy with the machines humans invent to kill one another.

Every one person of the 96 million lost in WWI and WWII should be grieved for. Each of them had valuable lives.

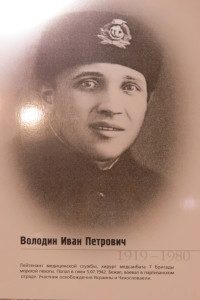

Volodin Ivan Petrovich

Volodin Ivan Petrovich’s son, the Director of the 35th Battery Memorial Museum.

Russians lost the most number of friends and family members in WWII,

about 27 million in all.

I noticed that the photo of a young man

at the bottom left corner of a memorial wall

may have been ‘photo-shopped’,

though the strong facial features

would have told the same moral or scientific story anyway:

war kills.

The Director of the Memorial gave us a tour,

and there,

in the basement shelters of the 35th battery,

Sevastapol sailors, medics and soldiers

were outnumbered and out-bombed

by German troops.

We were shown the portrait of one who miraculously survive

even the concentration camps,

Volodin Ivan Petrovich, 1919 to 1980.

The Director said that the young man

“finally got married and had children

and,

one of the children

is me!”

There was applause that history became flesh before us.

I was reminded of my paternal grandfather

who was also killed in WWII.

As I stood in a pantheon dome

where a moving sense-surround audio-visual presentation

depicted the 35th battery casualties

as stars and flickering flames which were finally extinguished,

I felt relieved to be able to cry for a few seconds.

Existence could be extinguished by war designs

that aren’t random at all,

but, frighteningly, laid out plans and protocols,

executed by collaborations,

and many complicities.

Altin, Director of La Richesse Museum in Bakhchisarai. The museum items of Crimean Tartars were collected from 35 countries through online searches and correspondences while Altin was in France.

In front of a former ‘New Method’ school for the sciences set up by Crimean Tartar intellectual Ismail Gasprinskiy. The chain over the door was so that students would bend low to enter, out of respect to knowledge.

Some of the young Crimean Tartars who hosted us at the Museum.

The Bakhchisaray Palace of the Crimean Khans built in the 16th century.

Tucked in a corner of Bakhchisarai in Crimea

is La Richesse Museum of Crimean history.

It is a unique museum that is internet-created,

in that its Director, Altin, collected its items from 35 countries

through online correspondence while he was in France!

Altin said, “We live in a different age, where so much is possible…”

suggesting that we need to be open

to possibilities which were impossible before.

Altin looked like a Hazara from Afghanistan, or a friend in Singapore,

or an Uzbek, or a lover of history or archaic objects,

anything but a minority person suppressed by the government.

They still served us tea though they were fasting,

and a few of the young volunteers

described their wish to be translators

and to set up ‘a big family’.

Perhaps because of the Crimean Tartar past

of persecution, massacre and exile,

they value an unbreakable family unit.

Again, the unique psychosocial make up

of every Crimean Tartar or human being, like Altin’s,

cannot be understood through the news.

We need to meet Altin,

and discover the gentle, thoughtful man who spent a whole afternoon with us,

the man who used digital tools to build a museum of his people’s history,

and to ask him,

“How are you doing deep within?”

Elena describes herself as ‘a mother with one daughter’, with no special interest in politics. She works with a charity NGO called ‘Blue Bird’ which serves children and disabled people.

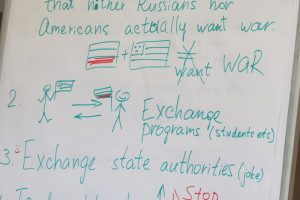

Some young Krasnodians who, with the U.S. delegates, suggested ways to build good relations.

An interesting idea from one of the discussion groups was to try ‘exchanging state authorities’: imagine Obama and John Kerry trying to get Russians to explain why a society should accept the gun-sale practices of the U.S. National Rifle Association because of a constitutional amendment.

Leave it to citizen diplomats and the youth of the world!

Elena, who described herself as ‘just a mother with a daughter’,

and ‘a simple citizen’,

works in a charity serving children and disabled persons.

She repeated three or more times that she didn’t mean to sound offensive,

but she observes that Americans seem so ‘self-assured’

that they “want to expand their ideas to the whole world,

even to those countries that don’t want their ideas”.

There were nods and smiles in the room –

nobody likes any form of ‘imperialism’.

Members of a youth group and the U.S. delegates

suggested practical things that could be explored to improve

U.S./Russia ties, ways that are peaceful, sound and mutual.

It was refreshing not to philosophize or argue,

but to find ‘earthly’ ways of connection

in the age of supposedly limitless connections,

one person at a time.

Russians love soccer too, including members of the Krasnodar Football Club,

so much so that a Russian businessman built a stadium (in the background and insert) and a football academy ( foreground ) to promote soccer and the Krasnodar Football Club.

The construction workers are Russians who are ethnic Uzbeks, reminding me of the Uzbeks in Afghanistan

Everyday, everywhere, every family seeks work and leisure,

common needs we all value.

We needn’t disagree on these,

as we can understand how our Russian friends want to

always bring enough home.

They waved at us spontaneously.

I was warmed by that gesture;

why would they wave at us strangers,

if not for goodwill to all humankind?

Kids play at a public fountain in Krasnodar, like kids in the U.S. would.

We stumbled into Juliana, a Leo Tolstoy fan at Like Hostel in Krasnodar. She and her friends started a Kindness Campaign in Krasnodar. Juliana believes in living by her conscience.

Artyom, an aspiring aerospace engineer, with his mother, became instant friends.

Juliana was immediately kind, welcoming and thoughtful,

was more concerned about the effects of a possible volcanic eruption

in Yellowstone National Park in the U.S. than politics.

She believes in living by conscience and having mutual respect,

to which Jan Hartsough responded, “…if we did that, we would not have wars.”

David Hartsough affirmed, “We’re not Russians or Americans or Afghans…

we’re all members of the same human family.”

“Politics and ordinary people are two different worlds,” Juliana added.

One of humanity’s glaring problem: politics divorced from reality,

from life, from people like Juliana

and Artyom, who became an instant friend

while waiting to board an Aeroflot flight to St Petersburg

where he was hoping to be an undergraduate of aerospace engineering.

His mother is his greatest fan,

both mother and son sincere, ordinary, special,

and ready to change their worlds.

Any awkwardness, antagonism or enmity in speaking with strangers?

No, those psychological disturbances

fill the whims and fancies of elites

who are panicking

because they’re discovering that they cannot rule

over the billion commoners’ wish for decent, loving lives.

The wreathed plots at the Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery in St Petersburg where about 470,000 victims of the Siege of Leningrad are buried.

Young Russians place flowers and ponder humanity’s unflattering past.

The scale of human conflict overwhelms us.

The eternal flame insists on our memory.

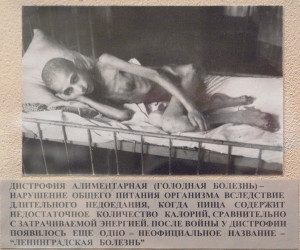

An archive photo of a Leningrad resident during the siege.

Residents collecting water from shell holes in St Petersburg.

A St Petersburg Street today.

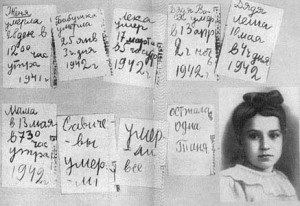

Tanya Savicheva and her diary from 1942.

Volodya, a St Petersburg resident, jogging when we were in Moscow.

420,000 civilians and 50,000 soldiers of the Siege of Leningrad

lie buried in 186 mass graves at Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery,

almost half a million people.

No wonder we felt as if the ground was sacred.

I looked at the flowers growing over each wreathed 1942-1944 burial plot,

and marveled at human resilience sprouting in resistance

despite many perishing from starvation,

some Russians today learning and speaking the language

of those who lay siege on their grandparents, German.

Our Russian guide, married to a U.S. citizen,

exuded a palpable disappointment bred by history,

embraced by grief,

and, I believe, soothed by forgiveness for the facts,

facts like those penned by the hunger-emaciated hand of twelve year old Tanya in 1942:

Grandma died, Leka ( sister ) died, Unlce Vasya died,

Uncle Lyusha died, Mom died, everyone died, only Tanya left.

Tanya could walk no more, and two years later, in 1944,

she was no longer ‘only Tanya left’. She died.

That may be partly why my room-mate, Volodya, would not waste any food

and would, with me, look for meals more economical than those at the hotel,

and who jogged in Moscow as he has almost everyday since 1966,

because we want a new world, a better one

than that which took some of Volodya’s relatives away too.

Volodya, thank you for reminding us that

remembering means

doing something today.

Lera and Ivan, undergraduate students who volunteered to bring Bob Alberts and I through St Petersburg.

Ivan introduced us to Jack and Chan Restaurant, where Singapore noodles were on the menu.

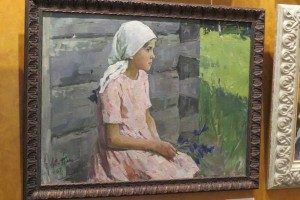

Lera in front of one of her favourite paintings displayed at the Russian Museum.

Ivan wanted to have a sincere smile for this photo, so I happily re-took it four times.

When I introduced myself,

Lera, an English major at university said,

“What? I can’t believe it? Talk to Afghans? Sure!”

An only child, her parents had high expectations,

so she felt stressed when she unsuccessfully tried Economics.

Knowing instinctively that we

ought to pursue what we’re passionate about,

now she aces her exams.

Quite matter of factly, she told Bob Alberts that

young Russians are skeptical about what the media ‘says’,

and that everyone is entitled to express their opinion,

like in the bus we took to the Russian Museum,

in which two middle aged ladies were upset that

Ivan questioned authority.

The Russian psyche is that ‘stability’ is sometimes more

important than personal freedoms, and that’s okay.

“To me, I feel free!” Lera quipped;

I could guess that from her countenance.

Ordinary Russians and Americans meet to discuss how to improve relations.

Both Russians and Americans were earnest and engaged.

Smaller group discussions provided further opportunities.

Next to the meeting place was a small private museum with paintings portraying the feelings of ordinary Russians.

The questions and answers were never simplistic,

and some answers were grey,

but the warmth of the participants, some academics, some activists,

guided all in the ‘heart-storming’.

Doesn’t everyone wish to have happy and meaningful lives?

There was a surprise visit by a Syrian diplomat,

“Syrians are harmed by all sides of the conflict

and the best is for foreign interests to leave us to resolve the crises,”

he said with clarity.

With so much minute-by-minute information today,

humanity’s challenge is to

listen,

not to the stale schemes of economic and political elites,

but to the billion other human beings.

Looking into people’s hearts is a way of listening,

So, I place before myself *a photo-video of ordinary Russians,

hoping that each time I see them,

I will understand one depth more who Russians are,

what our earth and human family is,

and who we are as fellow human beings.

Hakim Young, mentor to the Afghan Peace Volunteers